“Why can’t you park in the handicapped spot?” I asked my mom as she circled the parking lot of Fox’s grocery store in Hummelstown, Pennsylvania for the fifth time. It was an early Sunday afternoon in 1992, and apparently everyone who’s anyone in Hummelstown and Hershey was at Fox’s.

My mom slammed the brakes of her open-top Jeep Wrangler and for a moment I felt relieved that our search for the elusive parking spot was over. That relief shifted to confusion when she began crying and yelling at no one in particular. It took my eight-year-old brain several minutes to realize her ire was meant for me.

I had categorized her as handicapped. My words triggered a pain I had never witnessed before. To her,

they felt insulting. Insensitive. Cruel. I did something wrong, I internalized. I apologized profusely, but I didn’t understand exactly what I was apologizing for. What was so wrong with speaking the truth?

From that moment on, I didn’t dare mention my mother’s limp. I didn’t ask questions, she didn’t provide answers. I knew she walked with difficulty, but I didn’t know why. I never thought much about it because in my mind she was perfect. I didn’t know there was a clunky medical term for what she had. I didn’t know there was a possibility I could also be a carrier.

What I did learn that day in the Fox’s parking lot stayed with me into adulthood – pointing out a physical impediment was rude, calling my mom ‘handicapped’ was wrong, and it’s best not to speak of the things we cannot change.

Twenty years after the parking lot incident, I was marching down a long hallway of the American Idol offices in West Hollywood, California to ask my boss a question. Before I reached her office she shouted, “Hi Becky!” Moments later when I arrived at her door, I asked how she knew it was me.

“You have the loudest walk!” she exclaimed, sending my stomach into knots.

“It’s funny because you’re petite,” she elaborated, gauging from my reaction that my sense of humor apparently did not show up to work that day. She had no idea my loud steps were the result of nascent foot drop, or that I was in a state of denial about my health.

The questions and curiosity from others increased as I approached thirty. “Did you hurt your ankle?” “What’s wrong with your foot?” “Are you limping?”

Are you limping. Those words cut like a knife and fueled an insecurity so intense that I feared the rest of my life would be torturous. I used to think my mother was just sensitive, but I was beginning to understand her emotional reaction in the parking lot all those years ago. Now I was fielding questions about my changing body, changes I couldn’t control, changes I didn’t understand.

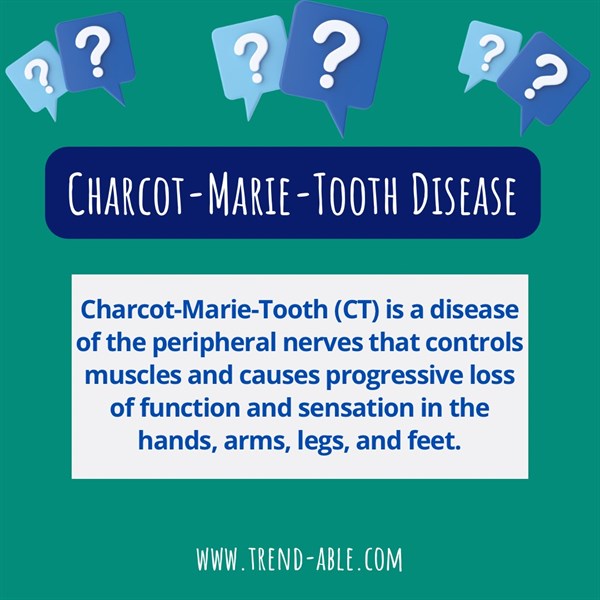

One night after work, from the safety of my bedroom in the Santa Monica apartment I shared with two limp-free roommates, I googled a variety of word combinations like ‘walks with limp,’ ‘thin calves’ and ‘abnormal feet.’ Eventually my search produced images of feet and calves similar to my mother’s. Without a doubt, this was it – something called Charcot Marie Tooth Disorder. A terrible name if you’d asked me then. A genetic disorder to be more specific. I held up my feet and examined my toes – they curled down like the freaky internet toes.

I thought this was simply the result of years of dancing in pointe shoes, tap shoes, jazz shoes, and ballet slippers. For twelve years I pointed my toes and critiqued my form in the unforgiving dance studio mirrors. Surely a dancer wouldn’t develop a neuromuscular disorder, I thought, that would be a cruel joke! I slammed my laptop shut and attempted to suppress my wandering mind.

While the acceptance process is presumably different for everyone, I think the lack of open communication and supportive language around CMT throughout my youth was a detriment once my symptoms emerged. I wasn’t emotionally or factually equipped to accept my new reality with grace. I was embarrassed, ashamed and terrified, and I felt alone with my fear. I wanted to keep my “invisible” disability invisible for as long as I could.

Carrying around that burden of secrecy grew exhausting, and it only deepened my shame. Occasionally I would broach the subject with my mom, desperate to talk to someone who understood what I was going through. Those conversations always elicited tears from her, but the root of her pain was never clear. Was she upset she passed it on to me? Is it possible she never fully accepted CMT herself? Is life with CMT commensurate with her dramatic reactions? If so, where did that leave me?

Instead of placing blame, I tried to contextualize this period in her life and yearned to understand why talking about CMT with her seemed akin to bringing up the Holocaust with a survivor. She was the product of a pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps family and a society that marginalizes disabled people instead of lifting them up. The 1970s were a promising time for women, and she was a beautiful, gregarious cheerleader who dreamed of attending veterinary school.

Then her split-capable, herkie-jumping body began to weaken with no road map or role model to reinforce her self-worth. She turned inward. Without the internet, she didn’t have access to other people living with CMT outside of her family. Around the time her symptoms emerged, her father died. Her father, the parent she inherited CMT from, was only forty-three. Her high school boyfriend turned fiancé allegedly broke up with her because ‘he couldn’t deal with it.’ No wonder it’s difficult to discuss – it triggers a traumatic time in her life, and no one ever helped her develop the tools needed to process that trauma, seek acceptance, and communicate effectively with her own children about it.

I can appreciate the circumstances that led to her inability to discuss CMT. She still managed to grow a successful business and raise three daughters to believe we could go after our dreams so long as we’re willing to work hard for them. With time though, I learned not talking about CMT doesn’t make it go away.

It took several years of therapy to transform the way I saw my disability and overcome my denial. Before therapy, I couldn’t understand why anyone would want to date me. I dodged my reflection in full-length mirrors and glass buildings. I ugly cried in bathroom stalls after every mention of my abnormal gait. Denial is a destructive coping mechanism but with some persistence, my therapist helped me rebuild my value as a human being capable of living a full life. We recalibrated the way I perceived CMT and my relationship with it.

I encountered women like Lainie Ishbia and Estela Lugo who spoke of their CMT with candor and humor, and it was the first time I felt at ease discussing my disorder. I devoured the repetitive online articles and tried to decipher pages of medical journals. I made an appointment at the Cedars-Sinai CMT Clinic in Los Angeles, my first visit with doctors since my self-diagnosis. Over the course of the three-hour clinic, I met with an orthotist who suggested Forrest Gump braces, a physical therapist who had me stretch this way and that, and an orthopedic surgeon whose charisma filled the sterile room.

This fast-talking man was Dr. Glenn Pfeffer, a top foot surgeon at Cedars-Sinai specializing in bespoke and complex CMT surgeries. I politely listened to his assessment, but surgery seemed extreme. I saw it as a last resort for severe cases, and at the time my symptoms were mild. Why would someone capable of wearing platform sandals to her CMT appointment risk a complicated surgery? I was convinced that as long as I stayed active, my symptoms would remain at bay. As I grew more comfortable, I also grew more vocal.

Naturally CMT did what it does best – progresses. In the years following my visit to the clinic I kept up with PT, worked out regularly and ate an annoyingly healthy diet. It didn’t preclude the sidewalk wipeouts or questions from strangers. After living in California for over a decade, the thought of trading in dresses and sandals for the limited wardrobe braces would relegate me to made me queasy. I continued to hike even though I increasingly looked like Gumby descending hills. My shoe options were dwindling. I took several embarrassing spills off the treadmill at Barry’s Bootcamp. I didn’t mind being different, but I also didn’t want to give up the things I loved.

There’s a difference between denial and stubbornness. Denial led me to despair. Stubbornness led me back to Dr. Pfeffer.

EXPLORING THE POSSIBILITY OF SURGERY

By the time I reached out to Dr. Pfeffer’s office five years after our first interaction I was living in New York and working at my dream job. I thought landing the Field Producer role on a respected late-night show in the city I always dreamed of calling home would overpower my insecurities with CMT, but burying myself in work only masked the pain. Despite some mental progress, I still struggled to accept there was nothing more I could do but succumb to a life of mobility issues and ankle-foot-orthotics (AFOs).

During my first winter in the city, I started googling CMT foot surgery while binging Christmas movies. It began as a curiosity and grew into an obsession once I discovered the endless success stories credited to Dr. Pfeffer. That charismatic doctor I dismissed while smugly perched on three-inch platforms. Those shoes were long gone as I read about his leadership in research studies and pioneering surgical methods. The man spoke on panels and at conferences, educating patients, parents, and medical experts about the possibilities of quality-of-life improvement for CMT patients. I watched the before and after videos on his Instagram page. I desperately wanted to be one of those patients showing off my Dr. Pfeffer miracle feet.

When I dialed the number listed on his Instagram page I reached a woman named Sue, and the call set the tone for a years-long process of working with supportive and knowledgeable medical staff. Until then, I rarely experienced such personalized care and compassion when discussing CMT with doctors. Cumbersome AFOs were presented to me so matter-of-factly by men who seemed to have no idea how heartbreaking it feels as a young, single woman to be told that’s your only option. Speaking with Sue, I felt emotionally understood for the first time by a medical professional. She didn’t question why I would prefer surgery to AFOs. She listened to my story and reciprocated with anecdotes about Dr. Pfeffer’s track record. After we hung up I burst into tears, overwhelmed by the interaction and filled with a cautious hope.

Before recommending an in-person consultation because I was out-of-state, I needed to submit foot x-rays and record videos of myself walking and moving my feet as directed. About a month later, I heard from Dr. Pfeffer. He was traveling to New York to visit family and offered to meet me in the city for a quick exam to save me the trip to LA. I was stunned; a doctor who cares this much about CMT patients? Was I dreaming?

CONSULTATION

We met in a hotel lobby in downtown Manhattan. I was heading to a fifth date with a guy I liked a lot; Dr. Pfeffer had about fifteen minutes before a dinner of his own. To ordinary passersby we probably looked suspicious, but we knew the stakes of this lobby exam. “Push your foot to the right as hard as you can. Push to the left. Flex. Can it go any higher? No. Push down as hard as you can. Now let’s see the other foot.” There wasn’t much to work with. He needed at least one tendon with moderate strength to attach to the top of the foot and the usual suspects were practically paralyzed. That familiar feeling of trepidation and defeat washed over me. I wanted to cry. Maybe I did. Feeling helpless was not an emotion I enjoyed but was getting to know.

Sensing my desperation, Dr. Pfeffer told me he never operates on someone unless he’s confident surgery will deliver an improvement. He’s not after a quota or a fortune, he must take a realistic approach. “Are you sure there’s nothing you can do?” I pleaded. He paused, then instructed me again to move my foot this way, push hard that way until at last, a positive reaction. The ball of my foot just below the big toe had almost all its strength. It was not a common tendon to transfer, and risky without at least one more to reinforce it, but he would give it some thought.

Dr. Pfeffer would later share how the visual of me exiting the Soho hotel and limping into the streets of New York on my way to a date stuck with him. To this day, I am blown away by how much that man cares. I was starting to think I didn’t matter to doctors. It is what it is, it could be worse, such is the fate of someone with a condition classified as rare. There are bigger fish to fry and diseases to cure. Suck it up, strap on some braces, and move aside. It was all so conflicting – am I making too much noise about my physical struggles, is it normal to feel this angry at my lack of options, do I simply retreat?

True to his word, he gave my case some thought. My entire body shook when I received a text a week later that read: “I think I can help your foot.” It was February of 2020.

I booked a trip to LA amid the early pandemic days to receive a proper examination and discuss my options. I was optimistic assuming this was a foregone conclusion and Dr. Pfeffer had to take my expectations down a notch. Under the fluorescent lights of his doctor’s office, my prognosis was less encouraging. I was on the border of surgical candidacy, hovering around a gray area where he’d typically draw the line at feet he feels confident operating on. Ultimately, he wasn’t ready to admit me as a patient and strongly recommended braces instead. Braces. Again. However, if I still wanted to pursue surgery after giving the braces a try, he would leave that choice up to me. Cautious hope persisted.

I reluctantly met with an orthotist, exposed yet another medical professional to my ugly cry as I tried on various braces, and dropped almost a thousand dollars on AFOs I didn’t want. That’s after insurance, a confounding amount for a medical device my preexisting condition requires, a medical device no fewer than ten doctors have insisted is my only option.

Considering the uniqueness of life in 2020 there weren’t many opportunities to take my new AFOs for a spin. The few times I did wear them, mostly to our remote studio as one of seven staff members with special Covid clearance, I noticed they improved my ability to lift my feet and smoothed my gait, but they also rubbed my calves to the point of bleeding and hurt my feet after a couple of hours. I wasn’t interested in finding the perfect pair of braces after spending a grand on my eyesore torture devices, but I didn’t want to make this decision to satisfy my vanity either.

To take advantage of quarantine I was seeing a virtual personal trainer with CMT, Chris Dito, who knows the capabilities and limitations of a CMT body better than most. One day I worked up the courage to ask his thoughts on surgery knowing there was some uncertainty. He was familiar with Dr. Pfeffer’s work and reassured me he’d be there on the other side to work on my rehabilitation. His stamp of approval validated what I already knew I would do. The next morning, I called Cedars to schedule my surgery.

SURGERY

Dr. Pfeffer agreed without hesitation. I followed through on my end of the deal, and it was his turn to reciprocate. I was impressed by the efficient process and clear communication regarding next steps, medical requirements, and physical and financial expectations to adequately prepare for out-of-state surgery during a pandemic. He called me personally to discuss the detailed surgical plan tailored specifically to my case. It’s a remarkable feeling to be enthusiastic about two trips to the OR. Has anyone ever been this excited to buy stool softener pills?

My left foot surgery was scheduled for December 2nd, 2020, a week after I’d wrapped-up the most ambitious shoot of my life for Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. I flew to LA on a Thursday, checked into my Airbnb, went to the grocery store, visited Dr. Pfeffer’s office for my pre-op appointment, took a Covid test, rented a knee scooter with a basket, prepped meals, and tried to relax in spite of everything.

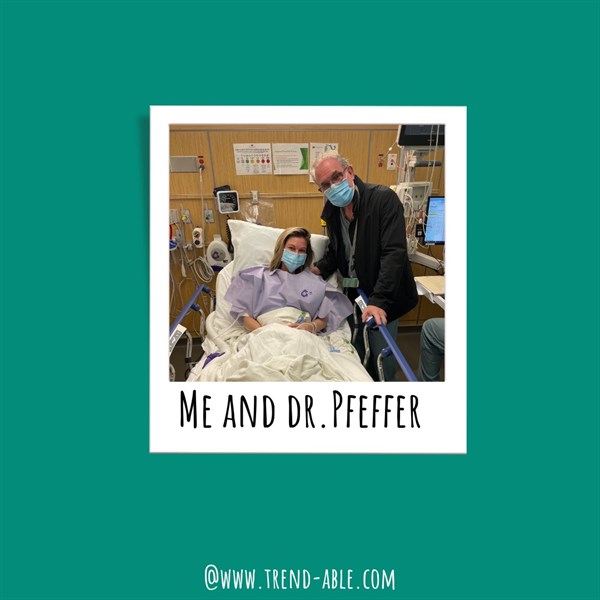

An Uber picked me up at 5:30am and I checked myself into the hospital before the sun came up. In my head I was the star of a Grey’s Anatomy episode cycling through teams of nurses, doctors, and anesthesiologists. When Dr. Pfeffer approached my hospital bed with an army of young doctors listening attentively, his encouraging words left me feeling worthy of walking confidently again.

The nurses wheeled me down a long hallway toward the OR where I met new nurses who spoke to me about New York and Broadway shows while someone placed a needle into my leg for the nerve blocker fluid. They started my anesthesia by warning me I would feel like I just consumed two glasses of wine, and this was a delight. With that, I was out.

When I woke up five hours later, my first thought was will I ever walk again? followed by I am going to pee in this bed. I will never forget my post-op nurse Patrick who dressed me and wheeled me to the bathroom and brought me ginger ale with saltines and listened to my blathering. I sounded like a drunk college girl on her twenty-first birthday flirting with the bouncer. I guess the anesthesia can have that effect. I learned he was a former college football player and I wanted to know how he ended up as Cedars-Sinai’s best nurse. I asked him if this was the largest cast he’s ever seen, does he have siblings, and is there more ginger ale? Dr. Pfeffer appeared just in time to cut off my drivel with the news that not only was my surgery a success, but if he had to give it a grade, he’d assign it an ‘A’.

“You mean, an A on the scale of all CMT surgeries, and not just my weird-ass feet?”

“That’s right,” he insisted. “Congratulations, you did great.”

Congratulations. This isn’t someone who emerges from the OR patting himself on the back for a job well done even though he should; he congratulates his patients because he believes they deserve the credit for getting themselves this far. Once I was discharged and began the wheelchair journey out to meet my friend Ashley, I shouted across the hospital floor, “Goodbye Patrick! Keep in touch!!!”

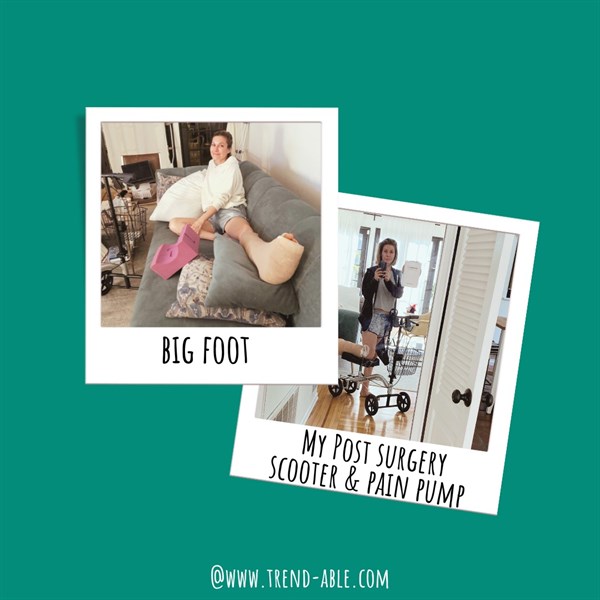

Ashley brought me safely home to my Airbnb and carried my body inside a la Weekend at Bernie’s. She ordered dinner and set me up on the couch with my knee scooter, pain pills, pain pump, blood circulation stimulator, foot pillow, head pillow, remote controls, and water. I felt like I was on drugs, mostly because I was, but also because the day was a dream come true.

RECOVERY

The pain pump is an invention for the ages. I couldn’t feel a thing until night number two when the nerve blocker started to wear off and I miscalculated the oxycodone timings, so I woke up in excruciating pain. Scrambling to the kitchen, I thought I would soon know what it’s like to pass out as colors melted to spots of white. I do not think this is typical, and had I remembered to take my pill earlier and ramped up the pain pump, it likely would have been avoided. In a weird way though, it served as proof that we did in fact reconstruct bones and move tendons and I am going to be different after this. By the next morning, my pain was under control again.

I remained in the large splint for two weeks then a smaller cast for an additional four. I couldn’t believe the power of the body when we removed the large cast and my foot responded with an upward motion at Dr. Pfeffer’s direction to lift as hard as I could. My foot hadn’t moved that way in years. He insisted it would only get stronger and increase its movement with time and rehab. Yet again, he was right.

Every recovery timeline varies, but I stuck out those four extra weeks in LA instead of risking a trip back to New York in the dead of winter as Covid surged. One more month of visits from LA friends with food and stories and Christmas decorations. Sometimes their kids made appearances – the knee scooter was always a hit. I watched movies, read books, and slept a lot. I developed a self-sufficient routine with the aid of my trusty scooter.

I equate the knee scooter with a basket to freedom. In addition to navigating an apartment, I figured out how to sweep (I hate mess) and perfected the three-point-turn radius out of the bathroom. There’s an infuriating scene in the first season of And Just Like That… where Carrie Bradshaw, recovering from hip surgery, pees in a bottle because Miranda’s too busy having sex in the kitchen to help her to the bathroom. While it’s possible that post-op hip-replacement patients aren’t supposed to use knee scooters, where are her crutches? Why no walker? Clearly none of the writers have ever put themselves through a surgery that renders you immobile. I’d sooner army crawl to the bathroom while doing Kegel reps than try to coax my stream of urine into a half-inch wide bottle opening. Sure, recovering from a serious surgery is easier with another person to assist with daily tasks (my friend Peter was a much better Miranda), but it’s doable and even empowering to manage most things on your own if that’s your only option.

When my four weeks were up in the smaller cast, I returned to Dr. Pfeffer’s office to swap that for a walking boot. We watched again in awe as my foot moved the way it was intended before CMT took over my body. He filmed the before and after videos to post to his Instagram with his signature “Congratulations” sign-off. My dream was now fully realized – I was going to make the grid.

NAVIGATING AIRPORTS

The transition to the walking boot felt awkward and painful at first, so I continued to use crutches for the first few days. I requested a wheelchair when booking my flight home, a move I highly recommend. The wheelchair handler brought me all the way through the gate where I boarded early, then down the ramp until I arrived at the plane door and switched to crutches to find my seat. Once in New York, a wheelchair was waiting for me at the gate and delivered me to my Uber. After six and a half weeks, I was home.

Eventually I downgraded to one crutch for support, and after a week I was moving swiftly in my boot through the streets and up the stairs. To gain back some independence and venture outside on my own for the first time in months felt liberating, albeit fleeting, as I would return to LA in a month to do it all over again on my right foot – the weaker foot.

Back at Cedars-Sinai to reprise my role on Grey’s Anatomy, I went through the familiar process of prepping my temporary home, renting my scooter, and clearing my medical tests. This time I was prepared for the size of the cast and how to coordinate my pain pump with the pills. My kindle was loaded, kitchen was stocked, and bath items complete with a trash bag and masking tape to protect my cast were placed (I’m sure Amazon has a contraption for this, but I found Peter’s trash bag solution sufficient). Dr. Pfeffer recommended using body wipes for the first two weeks of recovery when baths are prohibited, and no one told me to my face that I smelled.

This time I opted to fly back to New York while still in my smaller cast. Dr. Pfeffer understands not everyone can remain in LA for a six-week period and with one full recovery under my belt, I knew what to expect. The affable cast technician, John Domingo, drilled two small holes in my cast to alleviate pressure on the flight and referred me to a New York doctor for the cast removal. Taking taxis on crutches to my Manhattan appointments wasn’t as easy or glamorous as being driven in Peter’s Tesla, but nothing compares to recovering at home.

REHABILITATION

On April 24th, 2021, just shy of five months after my first surgery, I was out of my second boot and walking on my new feet for the first time. This moment was more terrifying than exhilarating as my ugly cry face reflects below. I wasn’t prepared for the instability and difficulty I faced as I attempted to walk again. This is a key moment to remind yourself that patience is paramount, as four days later I was able to venture out for dinner with friends (photo – right).

I began physical therapy several times a week. It was helpful enough to kick off my rehabilitation, but I saw the most progress working one-on-one with CMT trainer Chris Dito. He’s more expensive than a traditional PT facility, but while physical therapists may have heard of CMT, most don’t have a comprehensive understanding of it. It’s hard to beat a friendly and accessible virtual trainer who lives with the condition and rehabilitated himself through multiple injuries and surgeries.

I eventually joined a gym where I trained with someone in person (shout-out to Tony Gonzales, who studied CMT for me and dished the hot gos about all the gym bros in between reps). My mom and her partner surprised me with a Peloton as a birthday/Christmas/surgery gift and when I clipped in for the first time post-surgery, I felt a sense of achievement. Whichever type of exercise is right for you and your budget, it’s worth the effort to find something you can stick with for a while. After enduring intense surgeries and lengthy recoveries, why not do everything you can to maximize the results?

A YEAR LATER AND BEYOND

When people ask me when to expect to go back to normal life after double foot surgery, the answer isn’t cut and dry. It’s a long road that tests your patience and resolve. There’s no perfect time to make the decision to remove yourself from the world for several months, and I understand the decision is even more complicated if you have a family that relies on you daily. But for someone with CMT, it’s the greatest gift you can give yourself considering the unlikeliness of a cure anytime soon. The temporary sacrifice of daily routine and independence is a small price to pay for a lifetime of improved walking and getting back to the things you love.

The hardest part of that first year was adjusting to my lack of balance. CMT chips away at balance regardless of surgery, but I was naively thinking I would emerge with it improved, not worsened. It’s possible that five months in casts accelerates calf muscle atrophy, and as the CMT saying goes, “if you don’t use it, you lose it,” but I am not a doctor who knows this for sure.

I did notice incremental improvements with consistent training – my gait was smoother and faster, I could walk heel-to-toe for the first time in five years, but I still need to hold onto walls and lean against dirty subway beams when I stand still. This is the reality of the condition, and it’s important to realize that even with surgery some symptoms will persist. Yet if I had the option to do it all over again, I would without hesitation. The way you frame this decision and its potential impact will have a tremendous effect on how you interpret the experience.

About a year after my second surgery, I was back in LA for a shoot with legend Danny DeVito. Walking across the sound stage heel-toe, heel-toe, heel-toe, I received a text from Dr. Pfeffer.

“How is your foot?”

“It’s like you have a sixth sense or something, I’m in LA for a shoot!”

He asked if I had a window to swing by the office – he’d love to see how my feet were doing. I Ubered there from set that afternoon. The same office I approached nervously a year and a half earlier praying to whoever would listen that he’d take me on. We closed down the office exchanging stories like old friends at last call. As I departed that building for the final time, I reflected on an unbelievable journey that began in a hotel lobby.

I’d like to think Dr. Pfeffer and I forged a bond throughout this process, and he’d probably agree, but I bet he has a lot of patients who feel this way. It’s a testament to how much he genuinely cares about improving people’s lives. He once told me that CMT patients are his favorite – not because he views them as a science experiment, but because they tend to have the purest hearts. I can’t vouch for the purity of my heart, but ever since I was cast and boot free, I started dancing at home by myself and strutting down the street like Joseph Gordon-Levitt in that scene from 500 Days of Summer after he has sex with his crush. If that’s not pure, I’m not sure I understand the word.

This is a deeply personal story to share on the internet. There was a time, before I could fully accept CMT, when I asked the publisher of this website to take down my articles. I was more concerned with prospective dates finding them and judging me prematurely than I was with the potential benefits that stories like mine can provide to others going through similar experiences. It took a long time to learn that the benefits of discussing CMT openly far outweigh the false sense of protection that silence provides.

Acceptance and perspective differ for everyone navigating a disability, and we’re entitled to handle that journey on our own terms. Disability and beauty are not mutually exclusive, even though our society implies this more than it should. I have days when I feel inadequate. Then I remind myself what I’ve learned thanks to CMT and how it’s shaped me as a person. My mother now has a blue and white handicapped placard she occasionally hangs when parking lots are full. Our paths have been divergent, but they both point toward progress.

Becky,

Thank you for sharing your remarkable journey. The specific phrases you’ve chosen to express your feelings are written with such grace, transparency, & bravery, and I’m so proud of you.

<3

Thanks for sharing your story! My son has a rare genetic disease and some of the kiddos also have CMT. I wasn’t very familiar with it and found your perspective incredibly helpful. Thanks again for sharing your story, it’ll help so many others!

Thank you for sharing your story and for your genuine, humble spirit! I am so happy for you and you inspire me! I was diagnosed 1 year ago.

This article warmed my heart. I have CMT as well and Dr. Pfeffer has done all of my many surgeries. I highly recommend him and absolutely adore what him and his staff does for the CMT community. I feel such a kindred spirit with all his patients. ♥

I figured I wasn’t the only one to sing Dr. Pfeffer’s praises, he’s the absolute best! Thank you for the message 🙂

Amazing article with a relatable story for all of us CMT carriers! Thank you Becky for your thorough storytelling and I am so proud of you and your CMT journey – both physically and emotionally. Also, just wondering if your shoe options have expanded since surgery and if Dr. Pfeffer feels that your balance will improve with more therapy and time?

Thank you so much Crystal!! I tend to stick to high top sneakers because I walk a lot in NYC and they give me the most confidence, but surgery has expanded my sandal options. I even splurged on a pair of YSL sandals that I can walk heel-toe in without tripping, which is a dream. I still struggle in heels because my balance isn’t great but I’m sure others could make a low heel work post surgery!