There’s a video of me at my third birthday party. I’ve watched it so many times, it’s almost my own memory. I’m Shirley Temple’s 1990s doppelgänger in a frilly dress, my blonde ringlets barely held back by a strand of yarn. In the small swath of thick carpet not covered in wrapping paper and new toys, I’m shuffling along in my very first pair of high heels. They’re made of pink plastic and way too big for my feet. Someone places a pair of sunglasses on my face and calls out, “Hollywood!”. It’s obvious that I feel fabulous. I keep shuffling, concentrating on keeping my tiny feet in the plastic heels, never wanting to take them off.

Two years later, I was fitted for my first pair of leg braces.

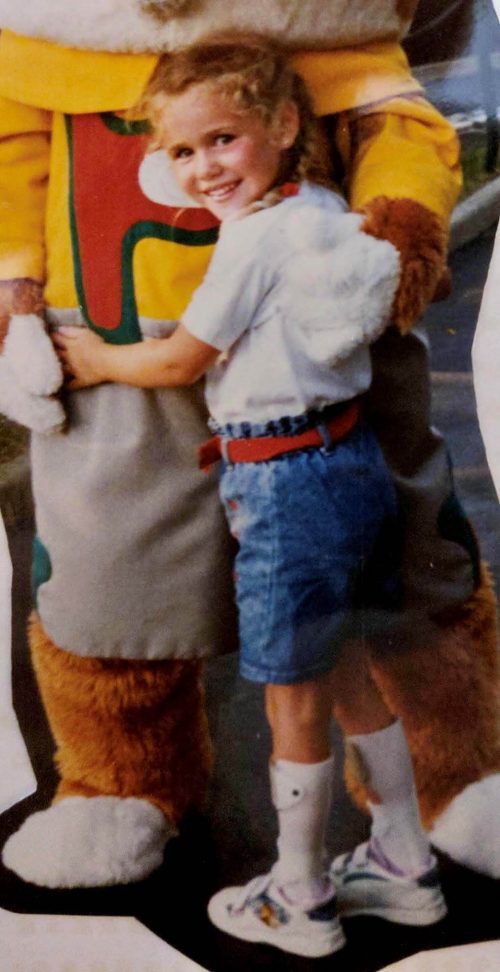

I have CMT Type 2A, a type that is typically more severe when it presents early. I was only two years old when my parents realized I had it. I joined the ranks of my grandfather, my dad, an aunt and an uncle, a cousin, and my older sister. Another cousin would be diagnosed with the disorder a few years later. Never steady on my feet and prone to sprained ankles, I received my first pair of leg braces at Riley’s Children’s Hospital in Indianapolis when I was five. My mom wiggled my velcro Nickelodeon sneakers over my new plastic legs, and for the first time in my young life, I stood and walked steadily.

The tradeoff for the ability to walk without twisting my ankles was never being able to wear the shoes I wanted. Unfortunately for me, Nickelodeon branded velcro shoes wouldn’t be en vogue forever. When summer came, my eyes began to fall on girls in flip flops, their straight toes painted pink or red or blue, and jealousy would rip through me as I looked down at my own feet, clad in socks, leg braces, and wide width sneakers. No one but me would see my toenail polish, applied as delicately and painstakingly as my peers. None of it seemed fair.

After getting that first pair of leg braces, and for most of my life, I have hated shopping for shoes. A trip to the shoe store meant an hour of my mom trying to wrestle shoes I didn’t like over my plastic AFOs, while we both sweated and she tried to explain to a minimum wage retail worker what a shoehorn was. Our “no” boxes towered next to us: too narrow, heel too high, too hard to get over my brace by myself. If a shoe fit and I could walk in it, there wasn’t any room left to say “no”, so I ended up with a lot of functional shoes I didn’t like. More often than not, I spent the ride home from these excursions looking out the passenger window, tears blurring the view of an endless stretch of fast food chains and retail stores. No matter how I tried to manage my expectations, a part of me always thought I would find the perfect pair, a pair I could walk in and love at the same time. Every time I came up empty, the disappointment swelled in my chest until I felt like I was choking on it.

Once, when I was in fourth grade, I stood in the middle of a Payless on a Saturday afternoon and lied to my mom about my ability to walk well in a pair of shoes. I loved them so much, I thought I could will them to work for me. They were black canvas lace-up open toed sandals with white piping and a slight wedge (hideous, I’m sure, but it was 1999).

“Really?” she had asked quizzically when I brought the box over to our pile.

“I just want to try them on,” I had replied, trying to sound nonchalant.

When my mom slipped them easily over my braces, I was sold. I didn’t care that I struggled to walk in them, that they had a cloth slingback that would surely slip off the plastic brace after more than a few steps. They fit over my braces, and they were coming home with me. I held the box in my lap on the drive home, like a new puppy I just couldn’t let go. I guessed this was the way most girls felt after a day of shoe shopping, and I could get used to it.

I wore the shoes to school on the following Monday, and all of my fourth grade friends oohed and ahhed the way I had hoped. Were they new? Where did I get them? Would I be mad if they got the same ones? I was so unused to kids asking me questions about my footwear instead of my leg braces, and I loved it. I walked to the playground at recess, buoyed by the approval of my peers, and careful to not get gravel dust on my new kicks. I stuck to the swings, partly because I needed to sit down and partly to keep my feet off the ground.

When the teachers on the playground called out that recess was over, I balked and let the swing come to a rest before forcing myself to stand. Had it really been thirty minutes already? The walk to the playground had worn me out, and thirty minutes of pumping my legs on the swing had not been restorative to my weakened muscles. As I started up the black pavement that led to the building, I felt my right brace slipping out of the side of my right shoe. The slingback had slipped off, the way I knew it eventually would. The left brace and shoe followed, until I was essentially walking with just my braces, only the front of the shoes holding on. I made it to my classroom, way behind the rest of my class, and pulled the slingback back over the back of my braces as soon as I sat down, breathing hard. Minutes later, we had a fire drill, and I had to make the trek all over again, my muscles quaking and the shoes falling off the entire time. I never wore them again. Mercifully, my mom never asked why my new shoes were collecting dust in the closet. I think she knew that they wouldn’t work out, that I just needed a win.

As I got older, I learned what worked for me, and bought the same kind of sneakers over and over again. I would wear a pair until they were ratty and disintegrated, and then find a similar pair and repeat the process all over again. I had a few precious flats that were wide enough for my brace, which I wore only when I needed to dress up. As my sneakers disintegrated, so did my muscles, and by my early twenties, my part time wheelchair use became full time. I still wore my braces to help with standing and transferring, but by my mid twenties, my right quad muscle had atrophied beyond use. I tried physical therapy, but the muscle didn’t grow. It was gone, and I was no longer able to even stand. So one day, after more than twenty years, I simply slipped off my braces and never put them back on.

The problem was, all of my shoes, meant to house my bulky braces were now way too big for my size five feet. As I searched online for some new, smaller sneakers, it dawned on me that for the first time in twenty years, I didn’t have to take my leg braces into consideration. I didn’t have to click the ‘Flats & Sneakers’ filter. It felt almost illicit to scroll through the pages of heels and boots, like I was trespassing on someone else’s land. Feeling a little silly, I ordered my first pair of heeled ankle boots, expecting to have to send them back almost as soon as they arrived. But on the day they came in the mail, I slipped them onto my feet and buckled the straps, and they fit perfectly. I stared at my feet in pure wonderment. I was hooked.

Shopping for shoes with the knowledge that I would never have to wrestle them over a leg brace or even actually walk in them gave me the giddy, joyous feeling I had had on that ride home long ago, the impractical shoes in their box on my lap. No shoe was impractical now. Where the possibilities had so long been narrowed down to a couple of boxes next to a hard plastic bench at Payless, they were now suddenly open and endless. I bought faux suede over-the-knee boots with a shiny gold block heel, sandals with high wedges, and bona fide high heels. I had a particular weakness for oxford style wedges that laced up, just as that pair of shoes in the fourth grade had. Only this time, they wouldn’t fall off. To go with the shoes, I started buying clothes that didn’t conceal my legs: midi dresses and skirts, shorts, skin tight pants that tapered at the ankle. For my entire life, I had been forced to build my style around practicality and utility. For the first time, I was building my own style based on what I actually loved, and I was addicted. I finally understood the Carrie Bradshaws of the world as my closet space dwindled.

Two years into my shoe revolution, pain began flaring in my right ankle. It was an old problem coming back, not realizing or caring that I was in a new phase of my life. CMT has a way of not giving a damn about personal revolutions. It’s very rude that way. As a kid, CMT had caused my right foot to turn in drastically, meaning I walked on the side of that foot, unable to keep it flat on the ground. I had corrective surgery when I was eight, a tendon transfer and pull at the same children’s hospital where I had gotten that first pair of braces. I was always informed that the surgery wouldn’t be the end of the road for me, that another surgery would be necessary later in my life. I was still growing and my foot was determined to grow sideways, beyond the confines of the screws holding it in place. The braces helped for a while. At age 15, I had a follow up with my surgeon, who said the foot still looked okay, even though it was beginning to turn in again, ever-so-slightly. We could wait a little longer.

By my early twenties, I was struggling to walk on the foot again. But I had aged out of the pediatric hospital, making my options more limited. I saw a local surgeon who had never treated a patient with CMT, and didn’t seem all that enthusiastic to take one on. So I got a new brace for my right foot instead, one that would pull it straight with a series of velcro straps, making it even more difficult to fit into a shoe. Eventually, that brace stopped working too, my foot turning painfully inside of it. It was a few months later that I ditched the braces altogether.

By my mid-twenties, in the full swing of my shoe revolution, it was undeniable that I needed surgery. I consulted with an Indianapolis surgeon who recommended ankle fusion. A tendon pull was no longer viable. Like worn out rubber bands, my tendons just weren’t very useful. My ankle would be in a fixed position, the surgeon explained as he held my foot tightly in his hands, demonstrating the position. In my mind, he was fixing me with a permanent leg brace. The thought made me panic, even as I met his eye and smiled. In the next few weeks, I pretended to consider and weigh my options, talked it over with my husband and my mom as though I was truly planning on the procedure. And then I did the mature, healthy thing: I ghosted the surgeon, declined all calls from his practice, and continued buying shoes. What was a little ankle pain, anyway? I’d dealt with worse, right?

In the next year, the pain began to increase exponentially. I would awake in the morning to an ankle that was discolored, the veins puffy from twisting with my twisted foot. My mom bought me an ankle brace to wear on the days it was really bad, and I found that I had run out of road. I was standing at the dead end I knew would greet me eventually. I needed the surgery, and soon, or it would only get worse and more difficult to operate. I made an appointment with yet another surgeon. I had gotten a letter in the mail informing me that the surgeon I had abandoned had left his practice. That seemed fair. At least he left a note.

The new surgeon recommended the same operation as the old one. I would need an ankle fusion to get my foot into a flat position. After many follow up appointments, and getting the remote opinion of Dr. Glen Pfeffer, widely considered to be the best CMT surgeon in the country, my ankle fusion has been scheduled for February 18, 2020, a little over three years since my shoe revolution began.

As the surgery date looms, I’ve spent more time than I care to admit scouring forums filled with ankle fusion patients, reading every possible answer to the same question asked by many: Can I still wear heels after an ankle fusion? The answer, predictable yet devastating, is probably not. I don’t know why I keep reading the forums when I already know the answer. I think it’s probably the same part of me that held onto a little hope every time I entered a Payless, knowing that I’d most likely leave empty handed. When I’m not scouring forums, I think about the months after surgery, when the cast comes off and I’m healed. I think about the day I’ll try on my beloved shoes, how I’ll feel and what I’ll do if my fixed foot is unable to slide into them. I can’t bear the thought of giving them away. We’ve had such a short time together. I know they’re just shoes. But that’s the whole thing. When you’ve been denied something as basic as footwear your entire life, it feels like the most precious thing in the world when you’re finally allowed to have it, like you’re finally a member of the club.

My life is about more than what I’m able to wear. Now 30 years old, I have enough wisdom to know this. I know my life will be just as full no matter what I have on my feet. I’ll still write and work and love and play in sneakers and flats. After all, I did those things for over two decades. I’m well-practiced at adapting. But it’s a hard thing when your body has been discussed and dissected in medical terms for a lifetime. When your feet had been poked and prodded, sliced and bent, hidden away in thick socks and plastic, it’s almost amazing when they become just yours. For this brief window of time, I got to decide what to put on my feet based solely on what I liked instead of what would work for my disabled body. I got to know what it feels like to have autonomy over my own body, to feel confident and sexy. But the amazing thing is, even though the window is closing, the lessons are staying with me.

CMT may dictate what I am able to wear, but it no longer has any domain over how I feel in my own skin. What I’ve come to realize is that the high heels, the boots, the wedges didn’t make me confident, they didn’t fundamentally change who I am. They served their purpose in letting me play, letting me discover what I like and to break out of the monotony of self pity. I know this, because now when I wear sneakers and flats, I feel just as good in my skin as when I wear high heels. That discovery of myself is what brought my confidence and my autonomy to the surface. I can be myself in whatever it is I’m wearing, because now I know who I am. There are a million ways to discover who we are and what we like. Shoes happened to be one way for me. But I am slowly realizing that it isn’t the shoes I am addicted to. I’m addicted to the feeling of entering a space that had been deemed off limits because of my disability. And I can keep doing that over and over again. It’s a feeling more exciting than finding the perfect pair of high heels.

Sites like Trend-Able are a perfect example of breaking out of the spaces we’re told to confine ourselves in. Sites like it didn’t exist when I was growing up. If it had, maybe I would have learned more quickly how to discover and embrace who I am. I am thrilled that young disabled women have this resource now. So while, yes, I am scared to go under the knife and change the life I’ve been able to live these last three years, I am grateful beyond measure that I’ll wake up in a world where spaces like this exist. A world where I’m not sitting on an island, that hard bench in Payless, feeling like the only one dealing with these hardships. A world where no matter what we’re able to wear on our feet, we allow ourselves the space to enforce our autonomy and exude confidence, both in spite of and because of the disorder that connects us.

Having CMT my whole life I related to every word in your story.

I am 70 years old and I basically have never walked barefoot, wore heels or was able to keep up with others in sports.

That said,I am still walking on my own two feet.

Yes I have balance issues , still can’t wear stylish shoes but I certainly realize how lucky I’ve been .

I had bilateral triple arthrodesis in 1962 , complete fusions and tendon transfers. It was quite an advanced procedure for the that time .

Thankful everyday to be independent and pray for a cure in the near future.

Bonnie

Hi Bonnie, Thanks for commenting. Funny, it was probably 1982 when I had both ankles fused as well. You have a great attitude! I’m sure it’s serves you well.

Thank you so much Monica for sharing your story and wise insights !

Your writing is beautiful and inspiring, you look radiant :-).

Thank you again, and thank you so much Lainie for making this sharing possible 🙂

Very warm wishes form cold Canada to all of you xx

Thank you for reading! It’s pretty damn cold in Indiana too! ?

Monica, you certainly have a gift for writing! I am older than you, but recall the shoe shopping experiences of my youth; my parents would go to the ends of the earth to find the one elusive pair of shoes that didn’t hurt, I could walk in, and were cute……. and then bought them in every color! My CMT also progressed to where I was walking on the side of my foot, unable to put it flat on the floor. Triple arthrodesis worked for me, and I’ve been well managed for about 30 years. I thought of Dr. Pfeffer ( I follow him on Instagram, though never met him) while reading your story and believed he could likely help you. Then as I continued reading, he IS going to be your surgeon! I am so excited for you! Thank you for sharing your story, and best wishes and speedy recovery to you after surgery. Will be thinking of you and sending good vibes on Feb 18. ?

Thank you so much for reading! Just to be clear, Dr. Pffefer is not my surgeon; I just made sure to get his opinion before going under the knife with my surgeon in Indianapolis.

This story had me hooked. You are strong and beautiful!

Thank you so much!

Loved this article so much. Monica the first thing I noticed was your smile and the sparkle in your eyes. “Great spirit”, I thought. I am relatively new to AFO’s and finding shoes although heels have been out for me for years. However, we’re human and I miss my flip flops and walking barefoot in the summer and then my boots in the winter. Lainie has inspired me and with guests like yourself, the inspiration circle just gets bigger. Thank you for sharing your story and we will be thinking of you in your upcoming surgery. You’ve got this, times a million <3

Love and Light ~

Thank you so much ❤️❤️❤️

<3

I love your writing style and attitude! You nailed the unique shoe angst of a female CMTer. Thank you so much for sharing this.

Julie

Thank you so much for reading, Julie!

We still have shorts and dresses, they can’t take those away! What a great read Monica so proud to be your sister. Love you xoxo!

I am mentally prepared to adapt my footwear again, but CMT will never take my dresses!!!! Lol love you too!

Monica you certainly have a gift for writing. I love reading your stories. I know your parents are very proud!

Thank you so much <3

This was so well written!! I could totally relate to your show shopping experiences. Thanks for sharing your story! ?

Thank you for taking the time to read it!

I loved your story and can relate In so many ways I have crps and finding shoes that fit don’t cause me more pain and are cute is probably the hardest thing ever

Thank you so much for reading. Sending good vibes to you!

Monica – Lovely and honest post – I’m thankful I wasn’t into shoes before CMT2 crept up on me in my 30’s. I’m finding ways to wear flat plate AFOs with custom orthotics in shoes that I’m not embarrassed to wear. I’m thankful for those search filters on larger store websites (I hope those department stores never go out of business), Hoka One One rocker tennis shoes and Zappos for their free, fast shipping.

It’s always a bummer when a shoe store we can rely on goes out of business! Payless going under was rough for me! But I am so grateful to live in a time where our online options are so vast. It’s so much better now than it was when I was growing up.

What a great article, thank you for sharing!

I’m 48 with CMT1A and recovering from right ankle fusion done 1/22; my left ankle was fused last year. While it’s a long road and takes a lot of patience (not my strong-suit), it was totally worth it and I can’t wait to see the results once I’m fully recovered from this surgery.

I will probably need an orthotic to straighten the forefoot but at least my heel is straight and my foot is flat on the ground. I had ginormous AFOs for 25 years that I tearfully fit into men’s too-big- UGLY EEEE shoes, as the only option I had.

Previously I was in pain daily, 7-8 out of 10 and now it’s barely a 2; truly life-changing!

Now I’m on to the next chapter and can’t wait to see the possibilities.

Be strong and best wishes to you!

Ahh it’s so nice to read people’s positive experiences with ankle fusion! It’s such a permanent solution, which makes it all the more terrifying. But comments like yours totally put me at ease. I am definitely ready to be in less pain, and to feel less “crooked”, if that makes sense! Thanks for reading! 🙂

I feel like I was mean to read this. I’ve just recently been told that I was a candidate for tendon transfer in my hands. I’m 44 and have lost extension in my fingers. I’ve been looking this past week at going to a cmt center of excellence for a second opinion. My top choose is Cedars-Sinai in California or the CMT COE in NYC.

When I read Dr Pfeffers name in your story it sounded familiar so I went to the cedar-Sinai site and it’s the Dr. I was hoping to see myself. I’m from Georgia so it’s a big trip. I would love to hear your thoughts on him and his office.

Hi DeShea! I got Dr. Pfeffer’s opinion remotely via Instagram. He is very active and responds to messages and emails. I’m in Indiana and was unable to take a trip to California to see him in person. Very grateful to have his vote of confidence before I go into the fusion surgery.

Oh wow! I didn’t know I could speak to him remotely. How do I do that?

I’ve been on the phone with my insurance for hours and he is out of network. Trying to get him approved but may take a while. I’d love to contact him!

You can find him on Instagram at @charcotmarietoothsurgery. Best of luck!

Absolutely love this! Fashion is so helpful for self-worth.

Thank you for reading! 🙂

Beautiful testimony from a fellow CMTer